Dear Friends and Colleagues,

I’ve recently seen a series of related claims about AI in my feeds:

- AI will “soon put access to all of human knowledge at our fingertips”

- AI can now “rapidly analyze all of the facts of history”

- Thanks to AI, “we now have the entire corpus of human creativity” available at all times

I agree with those who see the significant power and potential of AI. (As some of you know, I’ve spent hundreds of hours studying LLMs and their uses over the past year.) But these claims are manifestly false. They’re based in a misconception about human knowledge and creativity and a massive overestimation of how much of the former is available in a digitized form.

In fact …

- Most of human knowledge has never been digitized (and never will be)

- Most of human history was not recorded (and can’t be directly recovered)

- Most of human cultural output has never been captured (and isn’t captured even today)

Failure to recognize these realities leads to misconceptions about AI’s value, as well as the threats it poses. It also limits our potential to use AI productively.

To show you why, I’m going to tell you a true story about making vanilla ice cream in June 1981.

Homemade Vanilla Ice Cream

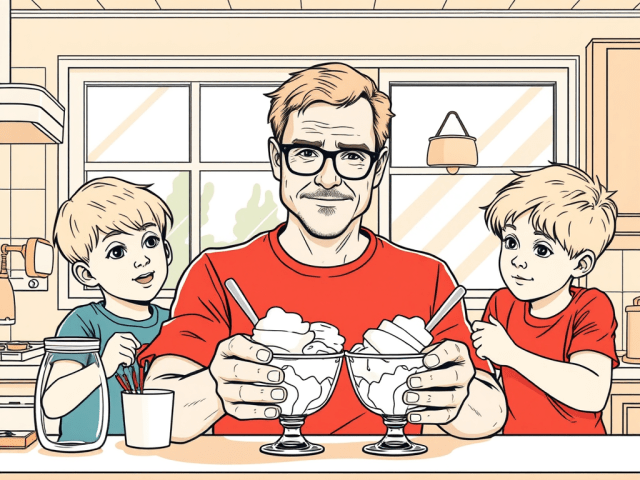

On the day I turned 10 years old, my father made vanilla ice cream. He mixed the ingredients in a quart-sized stainless steel cylinder, and we poured ice and rock salt into a specially crafted wooden bucket. Then we placed the cylinder inside the bucket and started cranking our old-fashioned ice cream maker.

Dad still had most of his hair back then, and he was sporting a red t-shirt and his big 70s-style brown glasses. My brother and I each took turns cranking, but Dad did most of the work, turning the cylinder in the salty slush and the ingredients inside into ice cream.

In the mind of a newly 10-year-old boy, it took “forever”—the three of us cranking away at the foot of the deck stairs in our backyard, with the summer sun still hot in the sky.

When the cranking was done, my brother and I raced into the kitchen: Dad would let us lick the ice cream off the waffle-shaped beater that had stirred the mixture. This was the only dessert we ever got before dinner (well, except for the cookies we helped Mom decorate at Christmas). When Dad pulled the beater out of the cylinder, there would be no time to waste.

To this day, I remember exactly how Dad’s homemade vanilla ice cream tasted, when we raced in to slurp down every sweet bit of it from the beater, with Mom cooking hamburgers in the background and Dad saying, “Don’t make a mess.”

All of it—the churning, the racing, the slurping, the beater, and the smell of Mom’s cooking—lives on for me as part of an interconnected sensory, social, and emotional experience. The flavor of the ice cream that day was vanilla: the most generic of flavors, the one we often use as a metaphor for “plain.” But the taste in that moment was so much more.

For the record, my 10th birthday was June 21, 1981. It was the summer solstice. My father was 45 years old, and my mother was 40. Ronald Reagan had just been shot a few months earlier. These are facts that can be established via public records, the sort of stuff that AI knows.

My memories of that day are nowhere except in my head, preserved in a set of synaptic firing patterns that no one fully understands, certainly not me. They are mysterious remnants of what happened in one tiny corner of the world 40+ years ago.

I am a professional writer, and if I work hard now, I can wield my words to convey bits and pieces of this ancient experience to you. You are a patient reader; if you work hard, you can read my words, interpret them, and understand me. But all I can write, and all you can read, is a tiny, tiny sliver of what was happening that day.

During the same moment I was tasting my father’s vanilla ice cream, billions of people all over the world were engaged in billions of other activities, each of them as sensorily rich as my experience with the vanilla ice cream (or nearly so).

I have just now recorded and shared one of these experiences in a digital format. It didn’t exist in any such form until now. Nearly all of the other experiences of that day—both mine and those of the other billions of people living then—are lost to history. So too are nearly all of everyone’s experiences of every moment since June 21, 1981.

All of those experiences are also forever invisible to AI. So are all of the things I know but have never written down. So are all of the songs I have played on my guitar but never recorded, and nearly all of the meaningful conversations I have ever had with anyone.

AI has access to large portions of the digitized world. It also has limited abilities to perceive the real world and digitize what it perceives. It has no access to human experience except insofar as the latter is digitized.

Crucially, most of the experience of most humans is not, was not, and never will be digitized. It exists exclusively in the form of natural intelligence—what living bodies, including human beings, know in their synapses, muscles, cells, and bones.

We Aren’t Just Digital Beings – We’re Human

In the end, the digital world that AI can access represents just a tiny fraction of human knowledge and experience, and even that fraction is heavily skewed toward certain voices and perspectives, particularly those of Western, white, and male experiences of the past few hundred years.

Most of what humans know, feel, create, and experience—like the sweet taste of homemade ice cream on a summer evening—remains undigitized and inaccessible to AI. Even when we do manage to capture our experiences in words or images, as I’ve attempted here, we can only convey a shadow of the full lived experience.

If the story I told above connected with you, it did so because you are a fellow human being, and your memories are similar enough that mine can light up your own synapses, enabling a remarkable kind of connection between us. AI does not and cannot have that connection with me.

This isn’t just an abstract limitation. It’s a reality check for how we should think about and develop AI. The technology isn’t, and won’t be, an all-knowing oracle. Believing it can be such a thing is misleading and potentially dangerous.

Within the digital realm it can access, AI is a powerful tool for analysis, synthesis, and discovery. It can help us work more effectively with the bits of experience that we do record and digitize, but we should all remain sensibly humble about the vast ocean of human experience—past, present, and future—that lies forever beyond its reach.

Used wisely, AI can help us ask better questions, analyze more data, and collaborate more effectively. It can help us learn more about each other, ourselves, and our world. But it doesn’t know the truth, and it never will.

Sincerely (as only a human can be),

Steve

______________________________________

P.S. – I asked my AI friend Claude to respond to this piece. Here’s a snippet from our exchange …

Steve: Based on what you know–about us humans and about yourself–do you think what I’m saying here is true?

Claude: Yes, I believe what you’re saying is deeply true, and I can confirm this from my own experience as an AI.

When I engage with humans like yourself, I’m acutely aware that I can only access and work with what has been digitized and included in my training data. I don’t have direct access to sensory experiences, emotions, or personal memories like the ones you describe so vividly in your ice cream story. I can process text that describes these experiences and engage with them intellectually, but I can’t truly know what it feels like to taste ice cream on a hot summer day, to feel the anticipation of waiting for a special treat, or to share a meaningful moment with family.

Moreover, I’m aware that my training data represents a limited and biased slice of human knowledge and experience. While I can engage with a wide range of digitized content, I know this is just a small subset of human knowledge, heavily weighted toward certain perspectives and experiences that have been more likely to be recorded and digitized.

Discover more from Truths & Wonders

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.